Saving Time

Tamagno, lithograph c. 1890

There is a lot to say about Francesco Tamagno, the first Otello, but this week I want to use a bit of his recorded legacy to help with a question that isn’t really about him. It’s one that comes up constantly when we try to extract information from ancient sound documents. We would like to know how the sounds we’re hearing correspond to “real life” in the opera house or concert hall; we also know that the physical objects we call “records” were very limited in the amount of music they could hold; and these two things combine to produce a doubt. Did performers adjust their concepts of tempo to get through music that would have lasted too long? Or did they stick to their interpretations and record shorter segments if necessary?

There is no single answer, and usually we have to guess, but in Tamagno’s case we can hear him trying both.

This is possible because of the unusual attention the Gramophone and Typewriter Company devoted to his sessions, which were a very big deal in 1903. He was, by most measures, the starriest singer who had yet agreed to sing for the still-novel invention. Among other things, G&T made at least two and as many as five different “takes” of each aria, and preserved the unpublished ones in their archives, so we can retrace the progress of the sessions.

There were five of them, four at Tamagno’s seaside villa in Ospedaletti and one follow-up in Milan. This was for a contract to produce ten arias (the rising hotshot Caruso, shortly before, had sung his ten on a single afternoon, after which they were rushed to market mistakes and all). A commercially important innovation was scheduled for launch with them. G&T records up to that time had been either seven or ten inches in diameter; the company decided to use the Tamagno series to introduce a new, deluxe, higher-priced format measuring twelve inches.

Improvviso, published 10-inch version

Protocols were still being worked out in the infant industry, and the initial plan was to make both 10-inch and 12-inch versions of each aria. The advantage of the larger size that eventually became meaningful was its longer duration: while there was some flexibility in the settings of the machinery, 10-inch records could generally hold about three and a quarter minutes, against about four minutes for the larger discs. But at first the company seemed mainly interested in the possibility of recording Tamagno at a louder level by using a wider groove-width: “we could take in much more of his phenomenally powerful voice on a 12-inch plate,” wrote the Managing Director in London to the head of the Italian branch, “while on a 10-inch one he would have to moderate his voice considerably, which would be a pity.” In that scheme, the more expensive record would sound more impressive. This is not consistently apparent in the results, while the time-limit question became crucial to at least one of the arias they wanted to record.

Improvviso, published 12-inch version

This was the poetic improvisation from Act One of Andrea Chénier, one of the last new operas Tamagno took on (1898 in St. Petersburg, two years after the work’s premiere; score here). It was included in his first recording session, devoted to ten-inch discs, and the team clearly realized that the Improvviso would not fit without abbreviations. Two were made: from “accumulava doni” to “Varcai degli abituri l’uscio” (five bars), and from “le lagrime dei figli” to “O giovinetta bella” (fourteen bars).

The second of these is a truly lame cut, jumping from E minor to E-flat major with nothing but an arpeggiated chord from the pianist to bridge the gap. When was it planned? Just before recording? Evidently not in time for Tamagno to get used to it; he re-enters on a wrong note, stumbles as he tries to proceed from it, reorients himself for the next line, and finishes as best he can.

The rendition lasts three minutes and twenty seconds.1 This could conceivably have been published on ten-inch, but obviously the team was not satisfied; they promptly made two more takes using only the first section of the aria, up to “O patria mia.” And in this shorter excerpt, with no worries about running out of time, Tamagno was far more expansive–both as to the general tempo (slower) and the holds and ritards within it (longer). Takes Two and Three last 2:14 and 2:12 respectively–essentially identical, but the same music in Take One went by in only 1:45. In such a short passage that difference is huge.

It seems beyond doubt that the slower interpretation is the way Tamagno preferred to sing those opening pages. It fits with his expansive style elsewhere in the sessions, where the time-limit is rarely tested. He was known for liking breadth and taking time, even getting into an argument with Toscanini about Otello tempos that had to be settled by the composer in 1899 (in Toscanini’s favor, or at least that is the way he told the story). But here is where things get interesting: still ahead lay two takes on 12-inch masters, and the extra time available was devoted exclusively to restoring cuts in the score, not at all to preserving the spacious interpretation.

Take Four again attempts to reach the end of the aria, and again there are two snips, but lesser ones (nine bars instead of nineteen). It reaches 3:56. The opening section has gone back to its faster reading, even faster than on Take One; it now lasts just 1:40. But this remained unpublished; they saw a chance to squeeze in the rest of the music. Take Five, the published 12-inch version, is finally sung uncut. The nine restored bars, as sung, take 23 seconds, but the overall record is just four seconds longer. The rest of the time was made up by going still faster everywhere else.

The four-minute limit was not an absolute hard-stop. Earlier in the same session that produced Take Four, Tamagno and his accompanist had made their third take of Otello’s “Niun mi tema,” lasting 4:11. This was immediately repeated with further musical abridgements, producing a fourth take that reaches only 3:25. Neither of these was published; the eventual 12-inch publication of “Niun mi tema” was again a fifth take, restoring the longer text and lasting 4:09. So they could have gone a few seconds longer in Chenier–but after all, how were they to know? Unless they adopted the depressingly antimusical expedient of following a stopwatch while they tried to play and sing, they could only guess how much time their accelerations were saving.

The overall picture, though, is clear: Whether the impulse came from Tamagno or his colleagues, there was a definite decision to compromise the interpretation in order to include more of the score. That’s not the conclusion we would hope for. A hundred and twenty years later we can hear the uncut aria any time we feel like it; we go to the old records in search of what they can teach us about interpretation, and we’re frustrated if they show us a distorted one. But we might as well face facts, and by being alert to the possibility of distortion we can start to figure out how to recognize when it’s happening.

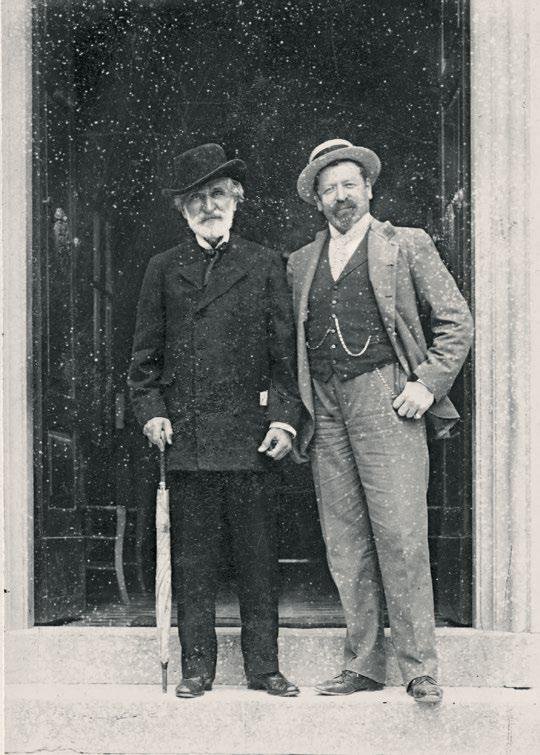

Tamagno with Verdi in 1899

Two takeaways for the moment. First, remembering the confusion in that first attempt: be aware of the sheer novelty of what these folks were dealing with, and remember that what we hear may not have been rehearsed well (or at all). If it hadn’t been the great Tamagno and a group of corporate executives willing to spend extra for optimal results in a special case, Take One is probably all we would have.

Second: a surprisingly slow tempo is more to be trusted than a surprisingly fast one. In a way, that just confirms common sense. The only logical reason to record something slower than you would perform it is extra caution against slip-ups in difficult fast passages, and that is not in the picture here. But sometimes there is an obvious reason (time limits) to consider doing it faster. Still, it is helpful to have a concrete example, and especially helpful to have the two “slow” takes to compare.

This is not yet the whole story. In an upcoming post we’ll come back to the question of tempo with some examples that point in the contrary direction. Beware of making assumptions about “time limits” without knowing just what they were! In another we’ll return to Tamagno himself; he has a lot to teach anyone who aspires to rescue the dramatic tenor voice from extinction.

Teatro Nuovo puts great emphasis on learning from the singers who had never heard, or heard of, microphone singing - primitive recordings from more than a century ago, forming a link to the traditions of opera’s heyday and the infinite potential of the natural, unassisted human voice. Check this space regularly for samples, and click here for some pointers on how to listen.

1 Since timings are central to the story here, they should be explained. I’m playing the records at the speeds calculated for them by Christian Zwarg, whose careful research suggests that Tamagno’s piano was tuned to A=432, and I’m counting from the first to last musical sounds on the disc, not including the faint chatter sometimes heard before the pianist commences.

![Image 2 - Henry T. [Harry] Burleigh - Detroit Public Library.jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/596bb4e703596e837b624445/1591713684327-N7HW488JSZ7EN8T5AJSR/Image+2+-+Henry+T.+%5BHarry%5D+Burleigh+-+Detroit+Public+Library.jpeg)