Vincenzo Bellini (1801~1835)

La Sonnambula

Sunday, July 20, 2025

Alexander Kasser Theater, Montclair State University

Thursday, July 24, 2025

New York City Center

Opera Semiseria in two acts

Libretto: Felice Romani, based on a scenario for a ballet-pantomime written by Eugène Scribe

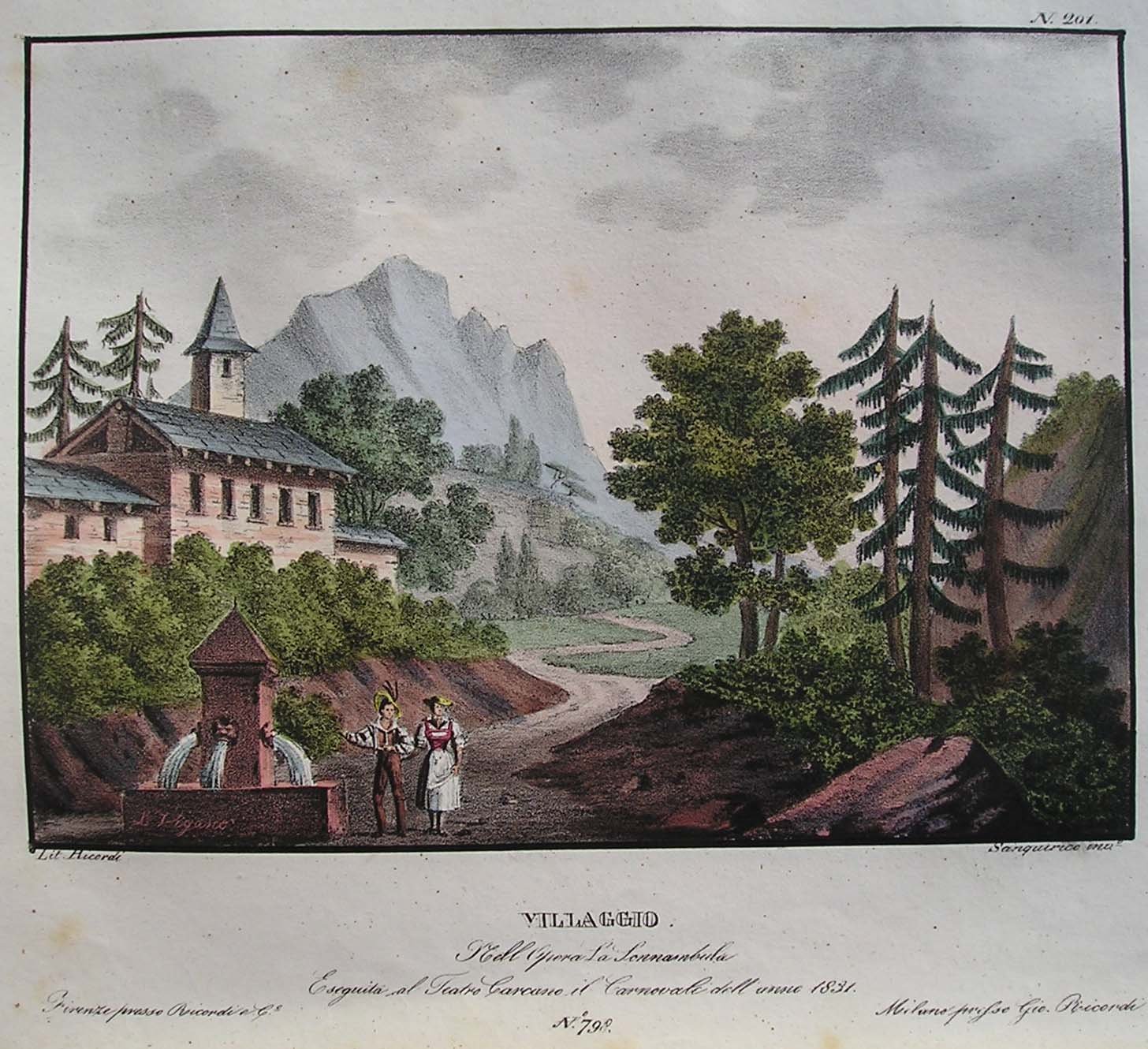

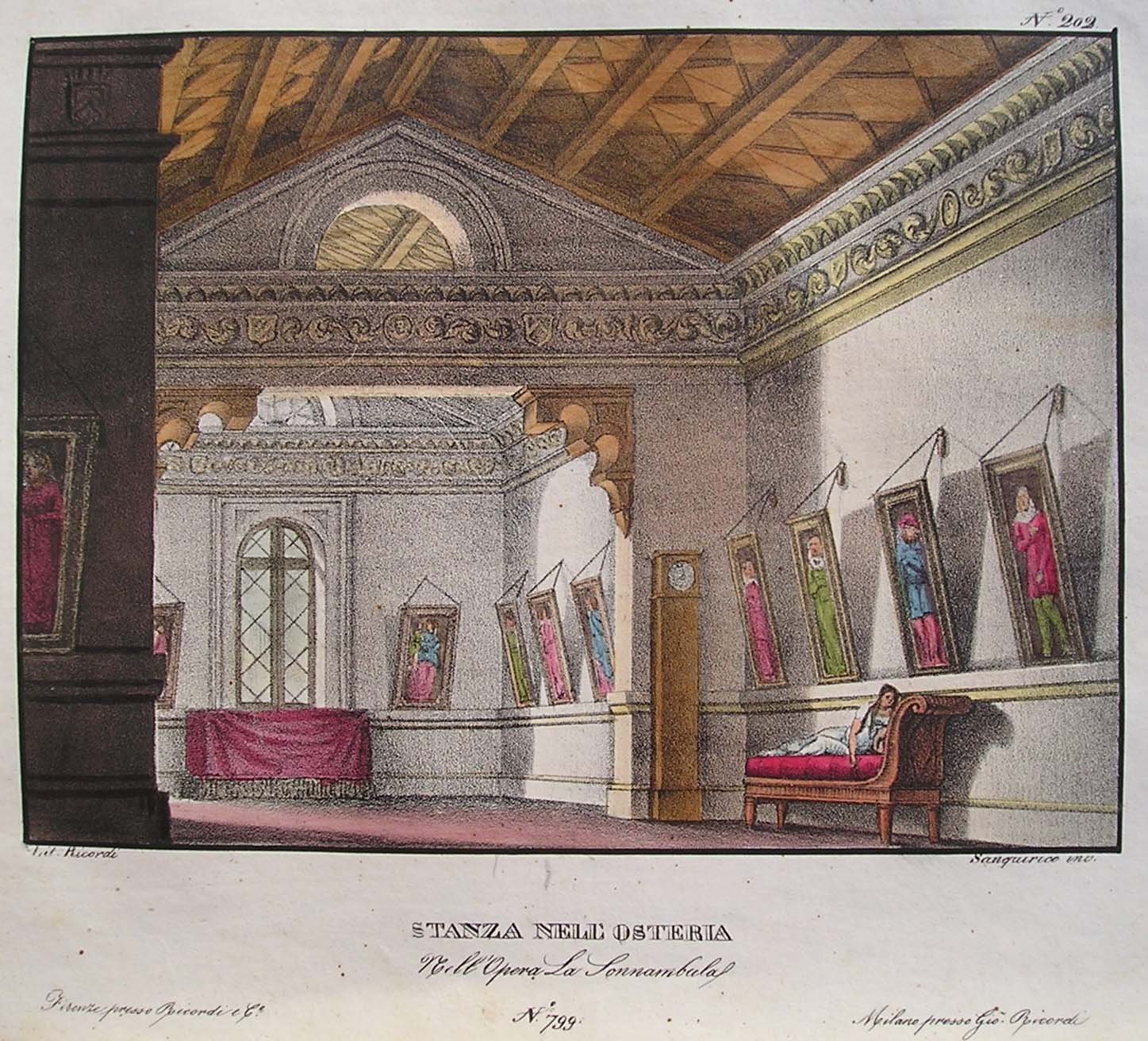

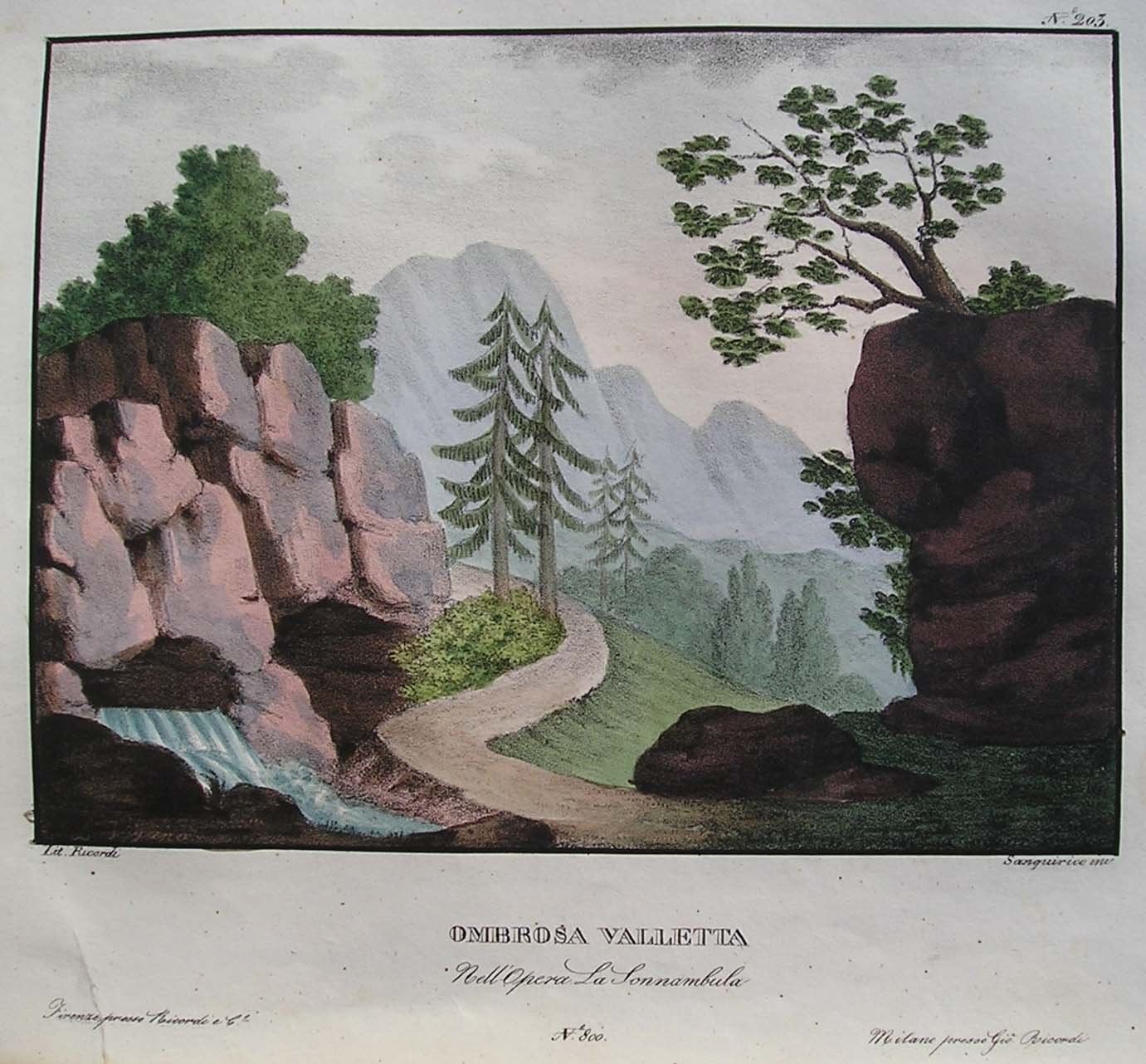

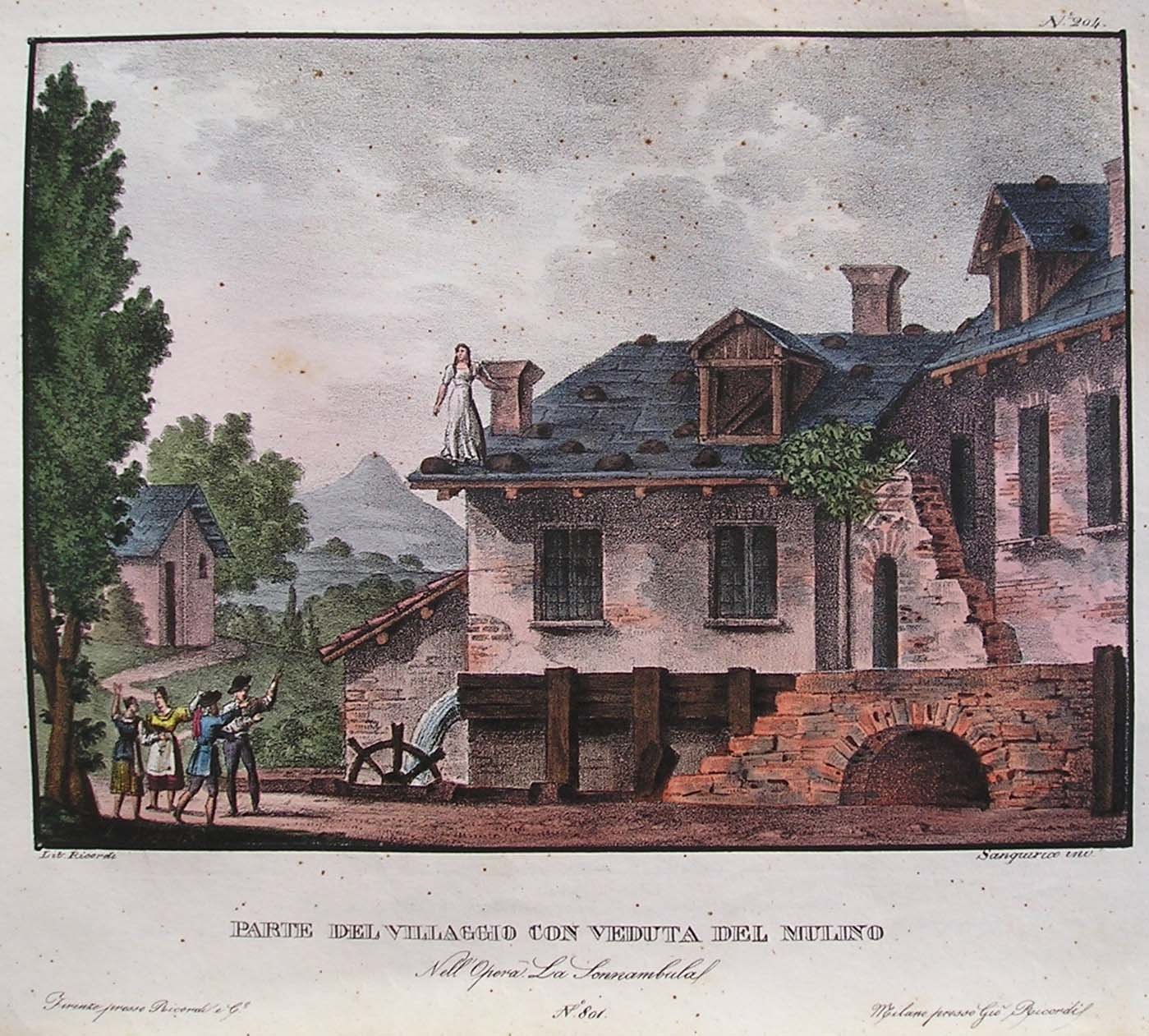

Premiere: 6 March 1831, Teatro Carcano, Milan

| Amina, orphan taken in by Teresa | Teresa Castillo |

| Elvino, wealthy landholder | Christopher Bozeka |

| Rodolfo, hereditary Count, long absent from the village | Owen Phillipson |

| Lisa, innkeeper | Abigail Raiford |

| Teresa, proprietress of the village mill | Abigail Lysinger |

Teatro Nuovo Chorus and Orchestra

Elisa Citterio, Primo Violino e Capo d’Orchestra

Will Crutchfield, Maestro al Cembalo

More Beautiful Than One’s Dreams

“one of the greatest composer-poet teams”

La Sonnambula is an opera better understood by audiences than by critics. Vincenzo Bellini and Felice Romani were one of the greatest composer-poet teams in the history of opera, comparable to Mozart with Da Ponte, Gluck with Calzabigi, and Verdi with Boito, and this work is perhaps the purest specimen of their ability to distill human emotion into verse and melody. The work’s naive candor has invited condescension and misunderstanding from some sectors of opera’s intelligentsia, but the public has never made that mistake, and has loved it for nearly 200 years.

“ The melodies take us to the heart of the situation”

There may be no other great opera that so fully entrusts its message to the one central element of melody, and that makes it a perfect candidate for Teatro Nuovo’s experimental style, which puts the singer in the driver’s seat. The melodies take us to the heart of the situation, and the situation is of perennial appeal: we see the heroine’s innocence, while everyone around her sees what they think is her guilt. We suffer with her, and rejoice with her when she is vindicated - and all of this happens in music “more beautiful than one’s dreams.” That is Wagner’s description - actually provoked by another Bellini opera, but uncannily appropriate for one set half in the dream-world.

Scenic designs for La Sonnambula. Alessandro Sanquirico, Teatro Carcano (Milan) 1831

“an immediate success”

La Sonnambula was composed in haste in the winter of 1830-31, after Bellini had to abandon work on a proposed Ernani when it became clear that the censors would not permit that inflammatory drama to be staged in Milan. The substitute opera was first performed at the Teatro Carcano there on March 6, 1831, and was an immediate success. It was Bellini’s seventh work for the stage, and he was not quite 30, but he was already the world’s most celebrated active opera composer.

Adelina Patti in La Sonnambula, c. 1860

(photographer: Camille-Léon-Louis Silvy)

Not that anyone would have called him that at the time: the title clearly belonged to Gioachino Rossini, whose most recent opera, Guillaume Tell, was less than two years old. Nobody guessed that it would be his last. Nor was it yet clear how far Gaetano Donizetti and Giacomo Meyerbeer would move beyond the copious journeyman works of the 1820s by which the Italian public knew them. Both had had successes - but Bellini, younger than either and late to enter the fray, saw his early operas circulate throughout Italy and penetrate the international market far more rapidly. Already his third opera, Il Pirata, was commissioned for La Scala; for his eighth, Norma, he was able to command the highest fee yet paid to an opera composer. Unlike any other Italian composer before Verdi, he was able to live (and live well) purely on his composing fees, without ever taking on an academic post or theater directorship.

“Something mysterious, elemental, intoxicating, and new.”

This had to do above all with a sense that it was Bellini and not his rivals who had stepped boldly out of the shadow of the great Rossini. In the young Sicilian’s music audiences heard something mysterious, elemental, intoxicating, and new. The newness was essentially melodic: there was something inexhaustible, by turns stimulating and narcotic, in the canto belliniano that set him apart and remains immediately recognizable today. “Song, song, and again song,” as Wagner exhorted in his essay honoring Bellini (the only Italian composer about whom he had admiring things to say). Verdi felt it too, and was moved to the same kind of incantatory threefold reiteration when he wrote in awe of his predecessor’s “melodie lunghe lunghe lunghe.”

“It appeals to something primitive and sensual”

These melodies have a strikingly distinct profile. They tend to be regular in rhythm, and that rhythm tends to match the most obvious, almost chant-like way of reading the lines of verse. They tend to dwell on repeated sequences of dissonance and resolution (“appoggiatura” is the technical term), with the dissonance often being longer than the consonance to which it resolves. This can have alternately a hypnotic, lulling quality (as in Count Rodolfo’s aria in Sonnambula or the choral response in Norma’s hymn to the moon), or a driving or battering effect (as in the war chorus in Norma or the angry ensemble at the end of Act One in Sonnambula). But in both guises, it appeals to something primitive and sensual, to an undertow of feeling rather than to the aspects of music that can be thought of as logical or directional.

“He needed the poetry always to be exceptionally beautiful”

This is not the only aspect of Bellini’s art, but it is the center around which everything else is arrayed. It is no surprise that the composer remained unusually faithful to one excellent librettist (Romani). His style emanated so directly from the melodiousness of poetry itself that he needed the poetry always to be exceptionally beautiful. Romani was Bellini’s senior by thirteen years and outlived him by thirty. His exceptional qualities as a versifier and his inclination towards straightforward, streamlined story-telling made him the ideal poet for the dawning Romantic era in opera, and his texts were set repeatedly by all the leading Italian composers up to, but not including, Verdi (whose music Romani never came to accept - probably sensing that its concision and forward drive spelled a reduced role for the independent beauties of poetry in the operatic mix).

“The story is simple enough to reduce to a sentence”

For their hastily concocted Sonnambula, Romani drew not on an existing dramatic or literary work but on the scenario for a ballet-pantomime by the French librettists Scribe and Aumer. The story is simple enough to reduce to a sentence: A village girl on the verge of her wedding turns out to be a sleepwalker, and when she wanders into the hotel room of a visiting nobleman, her fiancé and the community turn on her - until they all see her somnambulism with their own eyes, and wake her to beg her pardon.

“Reading it is not a dry duty”

It’s also simple enough to make some people think there’s not much there. A disheartening number have felt free to judge it publicly as “silly” or even “stupid,” to be tolerated for its pretty tunes and the show-off opportunities it offers a coloratura soprano. I think it is safe to say that most of these are people who have not read the libretto they are criticizing, and/or do not understand its words. But reading it is not a dry duty; the poem is endlessly beautiful, and plays its role in the opera’s enduring appeal.

“altered states of consciousness”

A fascination with altered states of consciousness - hypnosis, sleepwalking, hallucination, madness (transient or irreversible), even vampirism or enchantment - was expressed in countless plays, operas, and ballets of the day. This was essential to Romanticism, which had as one of its goals an exploration of the farther extremes, even disorders, of human feeling. That is easy enough for a modern reader to accept; what probably gives more trouble is the combination of unlikely coincidences and the sentimental simplicity with which they are treated. But “simplicity” must not be mistaken for “simple-mindedness,” and here it helps to understand the genre to which La sonnambula belongs, and of which it was the sole specimen to survive past the early 20th century: the opera semiseria.

“Semiseria” means literally “half-serious,” but it was something more particular when it emerged into an Italian culture that was long familiar with the contrasting poles of opera buffa and opera seria - comic and serious opera, each with its own traditions and typical characters and situations.

“It was an important step in the process”

Opera semiseria meant a musical drama with some comic elements and a happy conclusion, but with serious emotion along the way - including situations that could have ended in tragedy, and sometimes come right to the brink of it. It was an important step in the process by which music drama came to deal with the more volatile human issues, such as sexual jealousy, in a fashion more immediate than heroic opera’s vocabulary of formal honor on the one hand, or comic opera’s riotous hijinks on the other. Composers learned through it to treat subtler shades of emotion rather than crystallized extremes.

Equally important: it offered a chance to present ordinary people and contemporary situations in other than a purely comedic light. Mozart might have shown the way with Figaro and Così Fan Tutte, but those works were practically unknown in Italy until much later; the native composers had to discover this path for themselves.

“A theme runs through the libretto”

Several opere semiserie were hugely popular and influential in Italy, from Piccini’s La Buona Figluola of 1760 through Paisiello’s Nina (1790) down to Rossini’s La Gazza Ladra, Donizetti’s Linda di Chamounix, and Bellini’s La Sonnambula. Without them, later dramas like La Traviata and Rigoletto would have been impossible. But La Sonnambula was the only true semiseria to keep a foothold in the repertory continuously from its premiere (1831) to the present day.

“wide awake, living in the present”

Romani did not see this form as a reason for setting aside psychological complexities, but rather for concentrating and focusing them. A theme runs through the libretto that is far too consistent to have been accidental. Elvino, the bridegroom, is obsessed with his departed mother; he is late to his betrothal feast because he stopped so long at her grave, and speaks of practically nothing else during the ceremony. Count Rodolfo sings about lost days of youth and love; Lisa is fixated on a beau who doesn’t want her; Alessio is preoccupied with Lisa, who doesn’t want him. Teresa and the villagers gossip about the phantom that walks at night, the late Count whose castle stands empty, his heir who vanished without trace, and so on. The only person in the village who seems wide awake, living in the present and looking towards the future, is Amina - but she is the Sonnambula. When she sleepwalks into someone else’s business, she is doing what the rest of them do while awake. And since her awakening resolves most of the other problems, in effect she wakes up for all of them - or for us.

Is such analysis necessary to feel the emotional rightness of the opera? Of course not; it is just one effort to explain in part what nearly two centuries of life on the stage have already proved. Sonnambula’s critics have missed something; its public hasn’t.

“Sonnambula’s critics have missed something”

The critics may be right about some shortcomings in the technical craft of composition. One can concede that, and still concur with Rossini’s summation: “What the other maestri had, Bellini would have acquired in two or three more years. What Bellini already had, the others would never acquire.”

- Will Crutchfield

![Image 2 - Henry T. [Harry] Burleigh - Detroit Public Library.jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/596bb4e703596e837b624445/1591713684327-N7HW488JSZ7EN8T5AJSR/Image+2+-+Henry+T.+%5BHarry%5D+Burleigh+-+Detroit+Public+Library.jpeg)