Mother Schumann

Schumann-Heink in 1918

Ernestine Schumann-Heink really deserves a full-scale modern bio-pic. She was born working-class, abandoned young by a ne’er-do-well husband with four toddlers to feed and nothing in the bank, hefty of form and not blessed with a pretty face, and managed to become one of the most beloved opera stars in history. Also one of the wealthiest, until the stock market crash of 1929 took it all. Also a mother (eventually of eight) with sons in uniform on opposing sides of World War One (two of them perished). Also a movie actress, when talking movies came along in her seventies. Also one of the greatest mistresses of vocal technique and musical charm ever to leave records of her voice.

Along the way she was the first Klytaemnestra in Elektra (“Louder! I can still hear Frau Schumann-Heink” cried Strauss to the orchestra), a mainstay of the Bayreuth Festival in all the principal roles for contralto or mezzo, a Metropolitan Opera star from Ortrud in 1899 to the Siegfried Erda in 1932, and a Victor recording artist who took home $50,000 a year in royalties at a time when $50,000 meant what $1.5 million means today.

As Waltraute at Bayreuth, 1901

Those Victors - 115 of them published from 1906 to 1931, preceded by a few primitive Columbias and followed by a few primitive radio broadcasts - will keep her famous forever. What a singer! An ample low register, solid down to the low D of Der Tod und das Mädchen, with the purity and ease of a lyric soprano as she sailed up to top B-flat. Perfect coloratura at top speed, as she showed in the difficult triplets of Le Prophète and Sesto’s aria from La Clemenza di Tito. Impeccable trills. Imposing, steady fortes and ethereally floated pianissimos. Sovereign command of breath support (the last of her four recordings of a party piece from Lucrezia Borgia contains a messa di voce on upper F lasting 17 seconds, followed by a trill just one second shorter).

The icing on the cake is that she does all this with such spirit and imagination that through the ear alone we feel in contact with a whole personality. Schumann-Heink retained a kind of common touch, a hearty direct appeal to basic sentiments, that made her a favorite American touring attraction in recital. A record that sums it all up is “I und mei Bua,” a folk-style song in lower-Austrian dialect by Carl Millöcker. It’s a lilting Ländler with yodel refrain. Yodeling is a skill all its own, and doing it while maintaining “operatic” tone quality is for virtuosos only.

As Ortrud in Hamburg, 1890s

That one is “outgoing,” to say the least, but she could also do the opposite. Tchaikovsky’s “None but the Lonely Heart” is usually an operatic buildup to a generous climax; Schumann-Heink keeps it “inner,” sustained and quiet throughout. It’s not the only way to sing the song, but it is compelling and vocally gorgeous.

The only complaint I might have about the Tchaikovsky is that the voice is somewhat dimly recorded. The Victor company went through a longish phase in the early years in which it was over-cautious about making records that wouldn’t wear out. That meant keeping singers farther from the recording horn than some other companies did, with some loss of brilliance and overtones even beyond what was inevitable in the “acoustic” process. But Schumann-Heink survived into the microphone era, and though age took its toll on her sustaining powers and range (again inevitable), the new technology did allow for a satisfying close-up on the basic tone, which was unimpaired in steadiness and beauty as she approached seventy.

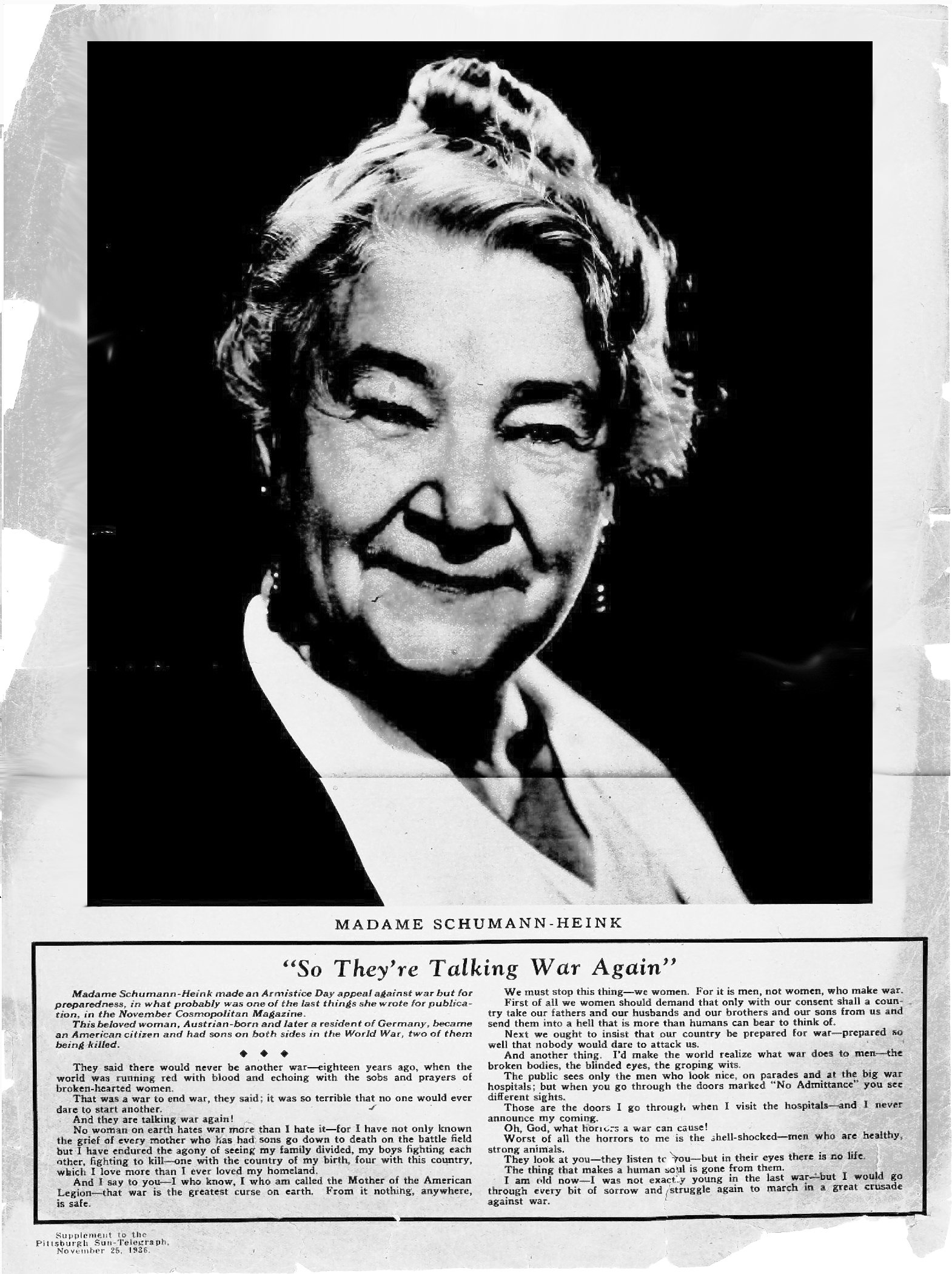

Anti-war statement from Cosmopolitan, 1936

She went on even longer, in radio, film and in her chosen mission of support for the war-wounded and the families of the fallen. One of her last Carnegie Hall appearances was at a concert for the Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League in April 1934, when she announced to the audience her receipt of a letter signed “True Friends of Germany” that told her “if you sing for the Jews, you will be killed. Take warning.” Her commentary: “They can’t scare me. I am too old for that.” She was already suffering from leukemia, and had barely two years left, but in the year of her death she signed a new film contract with MGM, and she passed away in Hollywood, working as long as her strength held. She had a lot.

Teatro Nuovo puts great emphasis on learning from the singers who had never heard, or heard of, microphone singing - primitive recordings from more than a century ago, forming a link to the traditions of opera’s heyday and the infinite potential of the natural, unassisted human voice. Check this space regularly for samples, and click here for some pointers on how to listen.

![Image 2 - Henry T. [Harry] Burleigh - Detroit Public Library.jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/596bb4e703596e837b624445/1591713684327-N7HW488JSZ7EN8T5AJSR/Image+2+-+Henry+T.+%5BHarry%5D+Burleigh+-+Detroit+Public+Library.jpeg)